“Cambodians are different. They are not hospitable,” Chu, a surveyor from Shanghai who was working in the northeastern Cambodian province of Ratanakiri, told me this when I stepped off my bicycle for a break. Later, as I cycled on the desolate red dirt road between Kratie and Banlung this thought stuck with me, bouncing around in my head like tennis shoes in a washing machine. I agreed with him and pined for the hearty hospitality I had been shown while hitchhiking in eastern Europe and Turkey. I rode this train of thought as I rode my bicycle, slowly and ponderously. I was tired and lonely, the road was unmarked, there were no towns or other landmarks to speak of, and my map was proving inaccurate. Hotels awaited me in Banlung, but I had another full day of cycling until I would reach them. Consequently I didn't know where I would sleep that night.

How did I get here? On this desolate road in the buttcrack middle-of-nowhere Cambodia, covered in red dirt, which seemed to permeate my pores and settle into every exposed crinkle in my skin. As I rode along, I imagined myself talking to someone who was thinking of cycling in Southeast Asia. What would I tell him or her? “Don't do it.” Yeah, that'd be the first thing. I had only been on the road for six days, but those were five miserable days. It rained constantly the first two days, despite this being the dry season, and even my long pants and wool sweater were not enough to keep me warm. Then after the rain, the shitty roads began. Dirt had turned to mud, a thick red mud which made traction impossible and pushing my bicycle a necessity at times. Soon after, I began to miss the mud as it was replaced by powder-light dust which came at me like a tidal wave of red dirt every time a motorbike, car, or truck passed me. The soreness abated quickly but still lingered on, especially in my ass, crotch, and lower back. But the worst of all was the loneliness. For six days I had spoken nary a word of English beyond “hello”. Instead I spent ten hours a day on my bicycle, my thoughts on constant repeat. Did I spend the time pondering my plans, my aspirations, my goals? Not at all. Something about the repetitive motion of the bicycle, the repetitive scenery, the physical exertion seemed to make any sort of philosophical pondering impossible. Instead I spent the time decrying my state and setting tiny goals for myself to keep me on the bike and cycling as much as possible. So even for mundane activities like checking the map, getting a drink of water, putting on my gloves, and applying sunscreen, I would make myself wait as long as I possibly could just to eke out every extra kilometer.

The entire day I passed by the same dusty landscape—spindly trees and tall grasses which were as coated in powdery dirt as I. Around 5:30 p.m. the sky started to darken and I knew I had about a half hour of good light left so I began to search for a house I could ask to sleep in. I stopped at the first house I saw and bought a bottle of water. The whole family was huddled on the ground using large metal soup spoons to scoop up and reserve some oil which had spilled on the packed-dirt ground. I isolated the matron of the family and as I paid for my water I made a sleeping pose, then shrugged my shoulders in a cartoonishly exaggerated questioning pose. She stared at me for a bit, then nodded vaguely. I smiled and said, “Akuhn.” I didn't know the logistics of my sleeping arrangement, but she had agreed, so at least I would not be sleeping on the side of the road that night.

I was coated in an opaque layer of red dirt and my junk was feeling a bit itchy. I guess the dried urine combined with tight bike shorts and long hours pressed to the bicycle seat was not agreeing with me. I asked where the bong khon was, only to find that they didn't have one. But I saw the eldest daughter splashing in some water in a small basin out back, so when she was finished I grabbed a half-filled water bottle and a change of clothes and squatted on the flat rock which acted as both kitchen sink and shower. They didn't have access to running water, so I used the drinking water left in my bottle to quickly rinse the most crucial areas.

I sat at a table at the front of the house with my journal and wrote as the light faded around me. There were three children in the family—two teenagers and a young girl. The youngest was inquisitive and came to peek over my shoulder as I wrote. I showed her the half-filled page, then put my journal down and began to draw in the fine dirt around us. First I drew simple shapes—a star, a heart—then started writing basic English words, pronouncing them slowly as I did. “Hello. OK. Bye.”

Just as it became too dark to write, around 6:30 p.m., the father pulled up to the house on the family's one motorbike. Almost immediately I heard the chugging of an engine turning over and then the constant whirring of a generator. The lights came on and the two teenagers, clearly well versed in this routine, turned on the television and stereo and popped a disc into each. As the mother prepared dinner, the remaining members of the family, as well as a few neighborhood children, gathered around the television. I can only imagine the name of the disc was Extreme Bloodlust 3 or something of the sort, as the “movie” consisted entirely of the bloodiest scenes from all the Rambo movies, spliced together with nothing so distracting as dialogue or exposition between them. Not that we would have been able to hear any dialogue. Instead, a mix of Khmer and American dance music blared over the speakers, including my favorite Khmer rap tune called, as far as I can tell, “Mien Loy,” which translate to have money though is used in this sense to mean payday. The lyrics, as they were earlier translated to me, are something to the effect of “I've got money, so I'm going to ride on my motorbike and buy some beef.” I appreciated the prosaic, mundane lyrics—a far cry from the seeming-hyperbole of their American rap counterparts. I tried to continue writing in my journal under one of the three light bulbs hanging from the bare ceiling, but the gruesome scenes on the television entranced me. As I watched Sylvester Stalone slash and shoot everyone around him, an American hip hop song I had never heard came on the stereo. The lyrics were pure poetry: “Don't want no short dick man. Don't want no short dick man. Eeny weeny teeny weeny shriveled little short dick man.” I smiled as I looked around at the four or five young children gathered around the television.

When the matron of the house came out with dinner—a big covered bowl of white rice and a smaller bowl of meat and vegetable stew—the neighborhood children left and the family relocated, their necks craned so they could still watch the television, to the dining table. The mother offered me a bowl, but I declined, saying, “At nyam satch. I don't eat meat. Nyam bai. Eat rice.” This simple phrase accounted for about half of all the Khmer I knew, and didn't entirely get my point across, as the phrase nyam bai, though literally meaning eat rice, is more commonly used to refer to eating in general—such is the importance of rice in Cambodian culture. But after a little gesturing she handed me a bowl of hot white rice and I topped it with soy sauce. I cleaned my bowl quickly but felt far from satiated.

So it was with a half-empty stomach that I prepared for sleep. It was about 7:30 p.m. and the family was closing up their house for the night. The mother brought out a tiny pillow, placed it on the table I had eaten dinner on, then joined her husband and three children on a wooden platform no larger than a full-size bed. The platform was covered in a flat, primary-colored plastic woven mat and sheltered by a light blue, rectangular mosquito net. The family huddled under one blanket and shut off the light. I contemplated my makeshift bed. Just thirty minutes prior I had eaten my bowl of rice on this table. Despite the early hour, I was tired, so I put on my warmest clothing—a pair of cotton pants, short sleeved t-shirt, and a wool sweater—and climbed up on the table.

I slept fitfully, turning from side to side whenever my hips became bruised, laying on my back until my tailbone ached. Around 2:00 a.m. my warmest clothes were no longer warm enough. I slept nonetheless.

The mother arose and began making rice around 5:00 a.m. and when I got up at 5:30 a.m., the kids were still sleeping. I shuffled around a bit awkwardly as I tried to say my goodbyes. I fumbled with my purse, but the mother would not accept any money. Instead she smiled quietly and gracefully as I tried to communicate my gratitude by pressing her hand and saying, “Akuhn,” over and over. I got on my bicycle and waved an enthusiastic goodbye. The air was soft and cool and the sun cast long orange shadows on the red dirt ground.

As I cycled on the silent road, reflecting on my night, I felt a familiar pang of guilt. The family had opened their home to me and allowed me into their lives. All I had left them with were some scribblings in the dirt, a few smiles, and hopefully a story to tell.

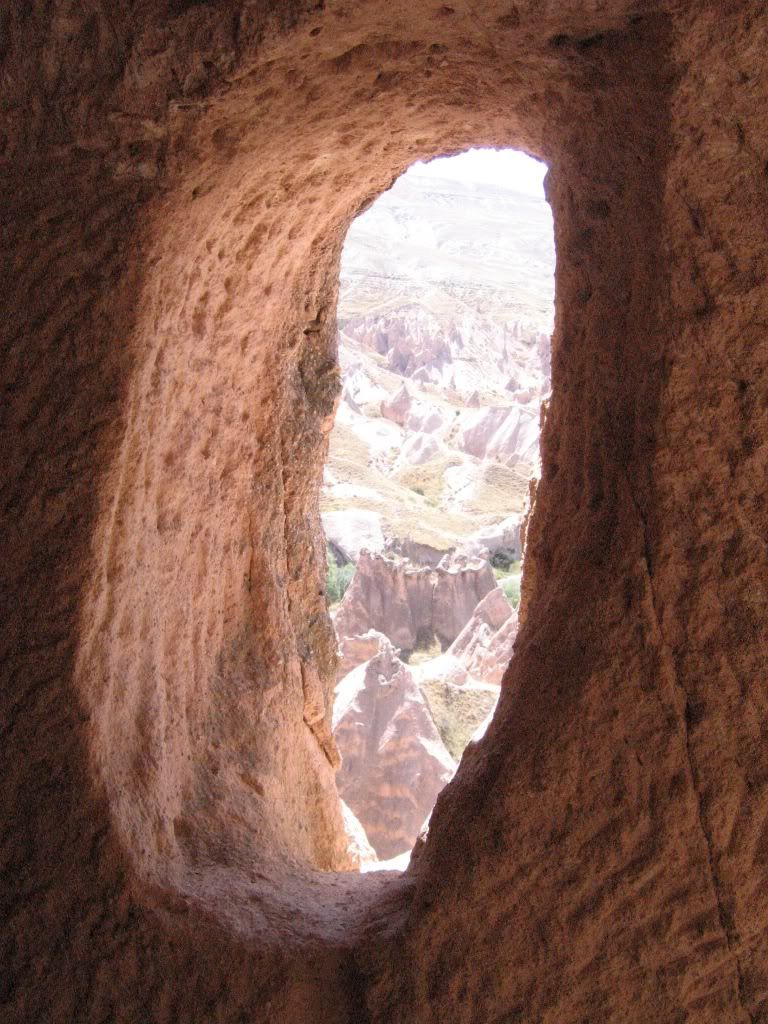

These thoughts occupied me as I peed out the window then crept safely back into the sleeping bag. Though it seems like a grisly image, the idea of this death actually tickled me immensely. What a way to go! I cherished the idea that it would first be a mystery. How did she get down there? How on earth could she fall out of a cave? And why are her pants down?

These thoughts occupied me as I peed out the window then crept safely back into the sleeping bag. Though it seems like a grisly image, the idea of this death actually tickled me immensely. What a way to go! I cherished the idea that it would first be a mystery. How did she get down there? How on earth could she fall out of a cave? And why are her pants down?