In a country like Lebanon, the paradoxes of being a solitary female traveler stand out in clear relief. It's not hard to imagine the inconveniences—the insatiable curiosity about my relationship status and sex life, the tendency of some men to see me as potential prey when I walk alone on a dark street, and the disregard for my ideas and opinions, no matter how well-formed. And though I have stories, and recent ones, about these inconveniences, today reminded me of a few of the joys and perks of being a solo female vagabonder. And as this is a topic that sometimes gets overlooked (and which I sometimes overlook), it's one I want to focus on now.

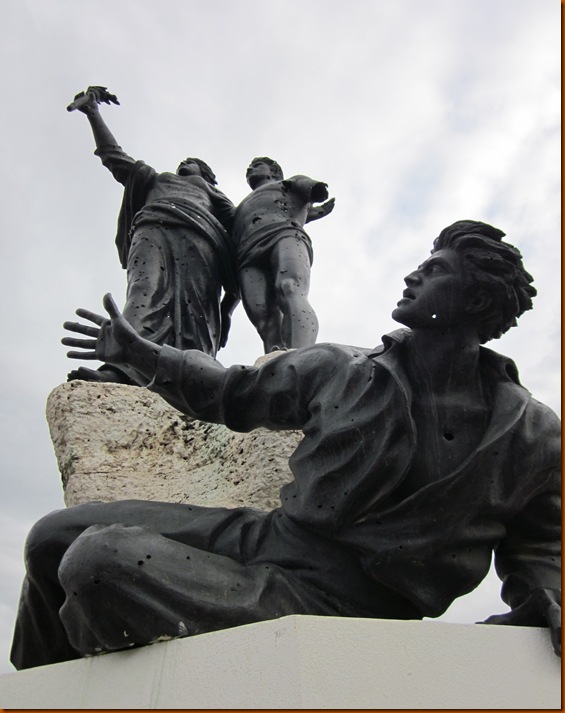

I traveled to Baalbek today, to the ancient pre-Roman city of the sun in the Bekaa valley of Lebanon. I wasn't sure what to expect from Baalbek. Especially since seeing Ephesus in Turkey which truly are spectacular and breathtaking ruins. But I found Baalbek to be quite stunning, especially in the warm, orange-ish light of the fading afternoon.

When I arrived and walked to the ticket counter, I saw the price was 12,000 LL so I pulled out two 10,000 LL bills but the man working at the ticket counter just smiled at me, took one bill and said, “You are a student.” I paused, processing the man's behavior before breaking into a laugh and thanking him, stating that though I wasn't student I was a teacher.

A man sitting near the ticket booth asked me, “A teacher of what?” “English,” I responded, and then we were off. The usual questions—where are you from, how long are you here, do you like it here, when will you go back?—but this time I didn't mind being asked. He was cultured and spoke perfectly and was charming and so the usual conversation was more interesting. He joked repeatedly about marrying me off to his son though said son was a few years younger than I, then about marrying me himself. “I'll divorce my wife,” he joked. Now don't take this the wrong way; I realize that without being there, without witnessing it, this conversation could seem obnoxious and all-too-typical. But he was kind and fatherly, gentlemanlike. His name was Mohammed and he had met Anthony Bourdain and showed me a picture they had taken together. He gave me his phone number and repeatedly offered me what would seem extravagant hospitality in most places, “but in Lebanon is normal. Our hospitality is famous.” He offered to come pick me up from the airport, should I ever return to Lebanon, “Just call me when you return and I'll be waiting for you at the airport.” He offered his brother's phone number in Chicago. “If you ever go to Chicago, just call me and I'll make sure my brother will take care of you.” So when he joked about me marrying his son, I laughed heartily—we both did—and when it was time to start exploring the Baalbek ruins, I thanked him wholeheartedly, we kissed on the cheeks three times, in Lebanese fashion, then he kissed my hand as I turned to climb the ancient grand staircase leading into the ruined complex.

How is this experience related my gender? A decent question. I don't think a young man would have so easily gotten such a warm reception. I think there is something about me, as a polite and soft-spoken young woman, that inspires parental affection in many of the people I meet. They long to protect me, to help me, to give me advice. And I, in turn, enjoy their stories and their genuine smiles, and the special treatment that often comes with those stories and smiles. I never expect extra help, and that is never the motivation for my kindness; instead I only expect kindness and some interesting conversations. I keep myself open, open to meeting people, open to conversations and it's not because those people have something to offer me. No, it is simply because I love people and I genuinely love talking to all sorts of people. Especially as a solitary traveler, I often fairly jump at the chance to talk to someone, anyone, to exchange a bit of kindness and affection with someone.

Once inside Baalbek, I walked through the bright and looming ruins, the huge standing columns sending their shadows down on me. The site was near-empty except for a small group of Eastern European tourists and a large group of Lebanese students in their late teens or early twenties. It didn't take long for one of the braver guys to approach me and ask where I was from. What he actually asked was (in English, no less), “Are you from Lebanon?” For a split second, the old Sarah threatened to emerge, the Sarah who would have quickly written him off or been brusque with him, seeing such an interaction as a waste of time. Instead, I laughed and told him. “Of course I'm not Lebanese, you know that otherwise you wouldn't have asked. And where are you from?” I flashed him a big smile. “We are students from Lebanon. Can we take a picture with you?” I responded in the affirmative and as we parted ways, he told me, “You are so kind and you are beautiful...” he trailed off so that I could barely catch the end of his sentence as his friends dragged him away.

Over the next hour or so, as we all wandered separately around the site, I would run into his friends and fellow schoolmates (one of whom told me proudly, “I'm from Canada. And Ukraine!”) and towards the end we met again, this time near the exit and it seemed that all the boys from the school were there and soon I was surrounded by about twenty or twenty-five young men, all looking at me, smiling with me, asking me questions, trying to make me laugh. It is impossible to describe just how much of an ego boost it is to be the center of so much attention, so much youthful male attention. As a traveler, it is often easy to tire of being the focus of curiosity—of receiving stares, countless 'hellos', all-too-personal questions—but the truth is that when that curiosity dries up, when you are in a foreign country surrounded by people going about their lives without a glance in your direction, after the initial elation of being left alone you really begin to feel lonely. You miss the conversations, the human interaction. You even begin to miss the impertinent questions and piercingly shrill 'hellos'.

The boys asked me about myself and I asked them where they studied. When they found that I was staying in Beirut, where they all lived, they tried to convince me to meet up. “We can hang out!” one boy said, using idiomatic English with ease. But when I found that they were still in high school, not the college students I had originally mistaken them for, I put an end to that notion. Nonetheless, they offered me a ride back to Beirut with them, but I opted instead to remain at the site a little longer—to read, to bask. The setting sun was casting long shadows from the tall columns of the temple of Bacchus and I wanted to soak up the view a little longer.

The perks I experienced today—kindness and laughter mainly—may have nothing to do with my gender and everything to do with my attitude. Catching flies with honey and all that. But I suspect that because of my gender and because I travel alone, I am more often afforded a glimpse into other worlds. I am invited into homes, into hearts. Though I don’t have an example from today, I know being female allows me access into the lives of women, which in this part of the world are restricted domains. So when an opportunity arises, I don’t hesitate to play up whatever qualities seem most advantageous.

I know some might disagree with my behavior, may think that I shouldn't act differently in different circumstances—that I shouldn't alter my behavior in such a superficial way just to gain help or benefits. But I think that view is overly simple. If the very qualities which sometimes cause me danger—my vulnerability, my solitariness, my open and trusting nature—can also be used to my advantage, can also help me connect with people I meet, then why I should I not play up those qualities? After all, they cause me trouble whether I like it or not. I feel fully justified in turning them on their ears and exploiting those qualities for my benefit.

Epilogue

I wrote this when I was traveling in Lebanon a few weeks back and I read it now with an ironic smile. After a few uncomfortable experiences in Jordan resulting directly from my openness, my trusting nature, and (to be brutally honest) my attraction to male energy, I’m not sure if I will continue to play up these qualities. What’s worse, I’m not sure if I can continue to approach people and situations with the same openness I once did.

I’m still mulling all this over. I certainly welcome comments and feedback.