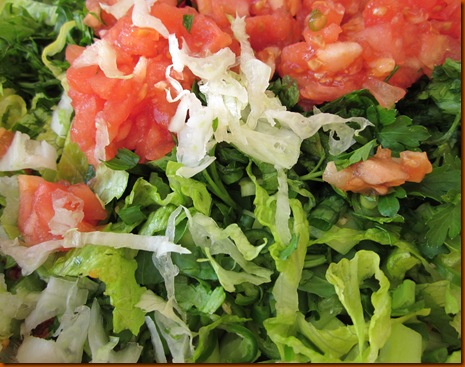

Downtown Amman looks like no other downtown I've ever seen. It is a mix of Roman and pre-Roman ruins, narrow streets, cheap clothing vendors, portable carts selling seasonal fruit (currently green almonds and strawberries), and sidewalks crowded with fully covered women, men wearing the red and white Palestinian-style headscarf, and a sprinkling of tourists. I walked through this jumble of people, greeted every few minutes by a friendly, “Welcome to Jordan!” to which I always smiled in return. I made my way past the old Hussein mosque and into a maze of narrow backstreets filled with fruit and vegetable sellers. There I spotted a man selling Jordanian sweets from a portable wheeled cart and one of the sweets caught my eye—a croquant-like bar of sesame and peanuts. I stopped to ask for one and we began to chat in a mix of English and my very limited Arabic. “You speak Arabic?” “Hafif, schwey.” He asked me to eat my sweet there with him and we continued our conversation. As we talked, someone bumped into me and so we moved the cart a little ways down the sidewalk. As I reached for my wallet to pay, the sweet seller insisted that it was free. Touched, I thanked him warmly and continued walking down the street.

A View of Downtown Amman

As I walked away, I reached into my bag to get my sunglasses and quickly realized my wallet was gone. I ran my hand through my entire bag again. No wallet. I had just been to the ATM because I needed money for my Thai visa and had about 230 JD ($328), as well as my ATM, credit card and drivers license in my wallet. In a little surge of embarrassment I realized I had a spare condom in there as well. Then I remembered that someone had bumped me from behind, jostling me and my purse and I immediately knew what had happened. I doubled back to the seller to ask if he had seen anything. Surely the thief could not have gotten far. I managed to explain that my money was stolen and the sweet seller's first reaction was to proclaim it wasn't him. I told him I knew that, but was just wondering if he saw anything. He made it clear that he hadn't and as I stood there, unsure of what to do next, he offered me, despite my strenuous objections, 5 JD so I could at least catch a taxi. I called my host, Mohammed, told him what had happened, and found that he was now on his way downtown. We agreed to meet at Hussein mosque. I thanked the sweet seller again then walked toward the mosque to wait for Mohammed.

Shortly after, a man approached me and told me that he had seen what happened—he saw my wallet being stolen. It was the man behind me, the galabeeyah seller, he said. I should go immediately to the police and tell them what had happened, and he pointed me in the right direction. He had been scared to tell me before because he didn't want the thief to make trouble for him. A minute later, another man approached me and said essentially the same thing. He had seen the galabeeyah seller take my wallet from my bag and he advised that I go to the police; he would accompany me but wouldn't make a formal complaint because he was afraid of the repercussions from the thief and the thief's well-connected family. “I hate to see this in my country,” he said, explaining why he had immediately come to me. “But I know who did it, and the man is a well-known thief.”

When Mohammed arrived he was steely and determined, upset that this had happened to me, but completely focused on resolving the problem. We went quickly to the police station—just a five minutes' walk away and were quickly ushered into the chief's personal office. Mohammed explained everything that had happened in rapid Arabic and when he finished, the chief asked me to explain. I recounted everything and soon a few police officers were sent to retrieve the galabeeyah seller and bring him in for questioning.

A covertly snapped photo of the police station

The chief of police, Colonel Alquran, spoke perfect, unaccented English. He was handsome and trim and carried himself with authority and confidence. I felt relaxed in his office; I felt in good hands. He asked what action I wanted to take and I explained that I simply wanted my wallet back; I had no desire for retribution. “Officially, we have no witnesses,” the colonel said, though he had spoken to the second witness who approached me. “No one wants to make an official complaint because they are worried about what might happen to them.” I assured him that I understood completely. “So you will make an official complaint against this man, explaining that you have reason to believe he stole your wallet, you felt him bump into you, and a few people told you it was he. You naturally can't remember much about these witnesses—where they work, their names, what they look like. Okay?” I agreed.

I hadn't gotten a good look at the galabeeyah seller, but within fifteen minutes of our arrival at the station, a man was brought into the Col. Alquran's office. Mohammed and I left the room for a few minutes, and as we walked back in, the seller spoke to me angrily in Arabic, asking me, “Why do you accuse me? Have you ever seen me before?” His question planted a seed of doubt. I didn't recognize him. Maybe he was the wrong man.

“Bad news,” the chief told us. “The man denies everything even though I told him that you didn't want to sue him; you just want your wallet back. Now negotiation is over and you will fill out the paperwork to make a formal complaint.” I could see he was disappointed. A formal complaint meant court visits, meant weeks of trial and paperwork until I could potentially see my money, my credit cards, my ID again.

But I still felt in competent hands. Mohammed told me about the last time he had been in a police station. His friend's car had been stolen in Amman and they went to report the theft. Three weeks later, the car was found near the Dead Sea, over 100 km away. A six on the license plate had been changed into a nine—a feat possible in Arabic—but the police had tracked the car down nonetheless.

As I debated aloud whether I should get to a computer to cancel my credit card immediately, I babbled something that one of the witnesses had told me. He had mentioned the galabeeyah seller's brother, implied he might be involved somehow. The colonel's face and demeanor immediately changed. He made a call, then turned to me. “We might get your wallet today after all. This man's brother is a well-known criminal, but he is also my eye. He provides information for me. He'll come here and I think he might be able to convince his brother that it would be best for him to return your wallet.”

The brother soon arrived—a muscular and tenacious man who spoke only to the chief and never once looked at me. I didn't know where to direct my eyes. If I stared at the brother, would he think I was being confrontational? If I didn't make eye contact, would he think I was a coward? I focused my attention on the chief instead. They spoke and though I couldn't understand what was said, I was again impressed by Colonel Alquran. His manner was strong, but fair. He spoke evenly and smiled once or twice, all without losing his authority or gravitas.

The brother left to try to find my wallet, charging out of the room like a bulldog. The chief and Mohammed seemed confident of success. When the brother returned empty handed, my heart sank. I had gotten my hopes up. But he raised his shirt and there I saw, tucked into his pants, my primary-colored Laotian wallet. He handed it over and the chief's assistant began to look through it thoroughly. My stomach churned as I remembered the condom stashed away in the back pocket. I leapt out of my chair and crossed the room, but I was too late. The assistant had opened and was searching through the zippered pocket. He emptied everything out, money, credit card, ATM card, drivers license, papers, receipts. I shuffled through them. Where was the condom? Everything was there except my emergency condom.

The mix of emotions I felt then was quite a cocktail. I was happy to have my wallet back, impressed at the efficiency of the police force, relieved the condom was not turned out on the chief's desk for all to see, and confused. Mainly confused as to what kind of a thief would have the delicacy to remove the condom before returning my wallet to the police, where many eyes—conservative male eyes—would ogle it.

Colonel Alquran explained that the galabeeyah seller and his brother had claimed to have seen the wallet being stolen and found it, but didn't know who the thief was. They were happy to return it to its rightful owner. This was the end of the matter. There was to be no paperwork because officially nothing had happened. Officially, my wallet had never been stolen.

The colonel gave me his phone number before we left, saying if I had any more problems, I should call him. He advised me to be careful, to carry less money, and to leave my valuables somewhere secure. All good, common-sense advice which I fully intend to follow. Until I become complacent and lazy again.

There was one last thing I wanted to do before we left downtown Amman, so Mohammed and I walked toward the Hussein mosque. I quickly spotted the sweet seller and thanked him for his kindness, Mohammed explaining that my wallet had been returned and that I was grateful for his generosity, but wanted to return his money as I really didn't need it. “Shukran,” I said. “Ma'a salaama.”

Jordanian sweets

Mohammed and I walked away and I thought how strange it was. Only two hours ago I had been in this same place. Two hours ago I had walked down this street, my purse full, my heart light. And here I was again, purse full, heart light. It was almost as if nothing had happened—nothing had changed. Well, that wasn't entirely true. I now walked with my purse in front of me, clutched in my hand.